It is common to hear in Indian strategic circles that the key to grand strategy in ensuring consistent high rates of economic growth. Economic performance certainly forms the basis for international political power. The higher a country’s rates of growth, the greater the resource base to spend on the tools of international power: military expenditure, foreign assistance, diplomatic resources, and so forth. A greater resource base also means fewer trade-offs, say between social and military spending (“guns vs butter”) or between capital and revenue expenditure in the military. China’s growth over the past three decades, and India’s to a lesser extent offer clear examples of the linkage between economic growth and political power.

However, it would be dangerous to presume that economic growth alone can substitute for a meaningful foreign policy.

The changing balance of power

The coronavirus pandemic is likely to have a devastating impact on the global economy. But some economies will recover more quickly than others, with implications for the balance of power. While the 2008-09 global financial crisis contributed to a period of economic stagnation in Europe and Japan, China, the United States, and (to a lesser degree than expected) India recovered more strongly.

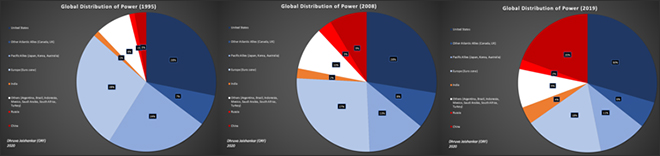

The three charts below show the changing share of nominal gross domestic product (GDP) among the G-20 economies (including the entire euro zone), which today comprise 84% of the global economy. China’s share, which was just 3% in 1995, grew from 9% to 20% between 2008 and 2019. In that same period, Europe’s declined from 27% to 18%, while the United States’ surprisingly grew from 28% to 30%. India’s share, a measly 1% in 1995, grew from 2% to 4% after the global financial crisis. While the United States has broadly held its share of global GDP among the major economies, the relative loss has been experienced primarily by Europe and Japan.

Scenario 1: A return to 2008-2019

The central question in projecting the economic distribution of power forward – in a more recessed post-pandemic world economy – is what kind of economic growth various major economies will experience as they recover. There are two possibilities to use as base lines for analysis.

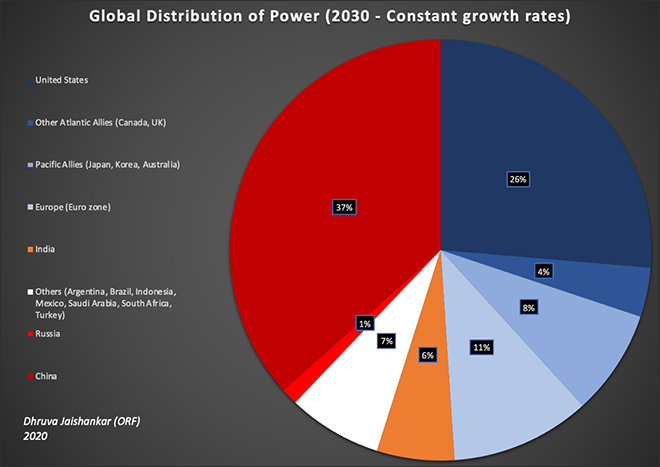

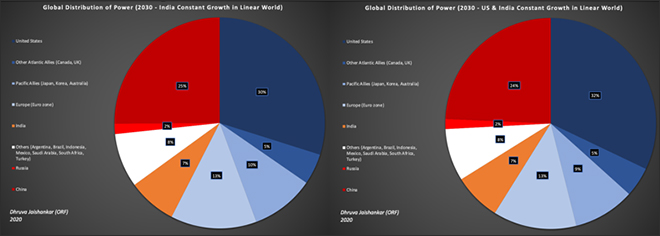

The first base scenario envisages constant rates of growth. For example, if a country averaged 4% growth between 2008 and 2019, this scenario presumes that it will maintain 4% growth between 2019 and 2030. Scenario 1 would appear both a very optimistic scenario and an ambitious objective. If this is projected forward for all major economies, this is what the distribution of power would like in 2030.

China will be the largest economy by some distance, followed by the United States. There are many reasons to doubt this outlook. One is that the coronavirus pandemic is likely to be far more devastating and disruptive than the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Another is that China’s rise in particular was showing signs of structural deceleration, suggesting that it would be harder to achieve high rates of growth as it evolved from a middle income to a high-income economy. Considerations such as debt and demographics also conspire against this possibility.

Nonetheless, this offers one very optimistic baseline. It would only be possible if certain technological innovations enable productivity increases, leading to a new wave of global economic dynamism. It may also require further expanding global market access, something that also appears unlikely at this point of time as global trade talks remain stalled.

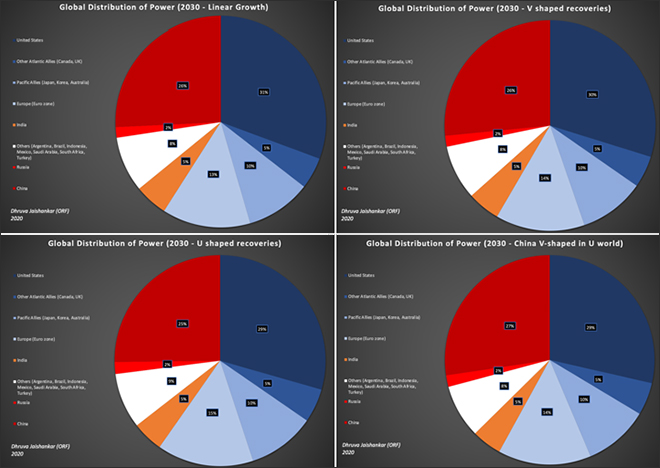

Scenario 2: Linear growth

The second broad scenario, only slightly less optimistic, involves linear growth. This presumes that if an economy added $1 trillion to its economy between 2008 and 2019 that it would add $1 trillion between 2019 and 2030. If we project this forward to 2030, it creates a Scenario 2. In this scenario, the United States remains the world’s largest economy, but China is a close second.

How much might the coronavirus pandemic affect calculations? Using the International Monetary Fund’s latest projections for 2020 and 2021, it is possible to project three variations on this scenario. The first variation is V-shaped recovery: a one-year contraction followed by a one-year rebound which in turn is succeeded by a resumption of linear growth. The second is a U-shaped recovery, involving a one-year contraction, one-year rebound, three years of recessed growth, and subsequently steady linear growth. The third variation is one in which only China experiences V-shaped recovery while all others experience U-shaped growth. As these four charts indicate, these variations make little difference to the relative distribution of major economies by 2030.

What will be far more significant, therefore, is whether economies can maintain constant 2008-2019 growth rates or a more prosaic growth that is consistent but decelerates with time. The difference between those two will ultimately come down to a combination of demographics, human capital, investment regimes, technological innovation, employment, and favourable market access.

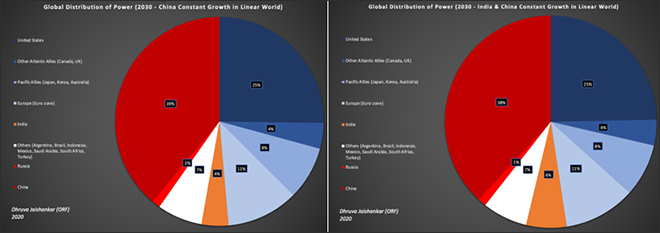

Scenario 3: Ascendant China

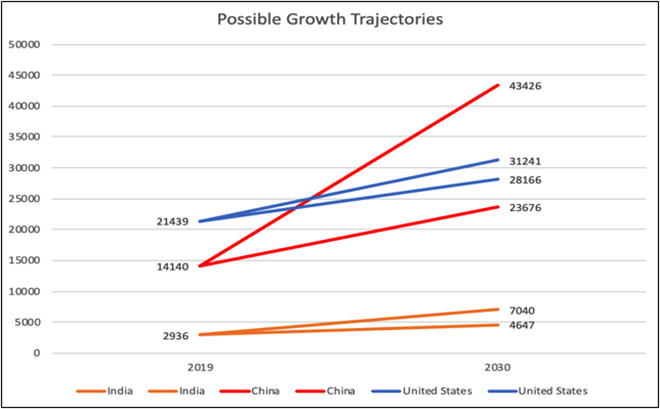

A third possibility is that China experiences a constant rate of growth for the next decade, while the rest of the world stumbles, experiencing only linear growth. In Scenario 3, China successfully transitions into a high-income economy and grows much larger than the United States. China’s economy would be almost 10 times the size of India’s. In a variation on that scenario, where China and India both grow at the faster rate, China’s economy is still over six times’ India’s size.

Scenario 4: Indian (and American) dynamism

In the most optimistic scenario from India’s perspective is that India maintains a constant 2008-2019 rate of growth as the rest of the world experiences a linear recovery. This would see India benefiting tremendously from global growth over the next decade and becoming a $7 trillion economy by 2030. But as Scenario 4 indicates, India’s economy would still be about one-third that of China’s. India will have narrowed the gap, but not as significantly over a decade as some might presume. In a variation on this scenario, if India and the United States both experience the higher growth rates over this period, it still does not shift the balance of power significantly.

Conclusion

These back-of-the-envelope projections should be taken for what they are. They do not consider extreme scenarios – so-called ‘Black Swans’ – which could possibly affect some economies: financial meltdowns, long-term recession and deflation, etc. Perhaps some countries will find that a recovery after the coronavirus pandemic is far more elusive than they had hoped. Or alternatively another set of emerging technologies may drive a new wave of global economic dynamism akin to the 1990s and early 2000s.

There are two broad conclusions to draw from this analysis. The first is that over the medium-term horizon, the severity of the coronavirus shock on economies, and their recovery, may not be as significant a determinant on future growth prospects as other factors. Specifically, the nature of growth over the next decade will be a more important determinant. The race underway by different countries to master and harness a number of emerging technologies – machine learning, automation, quantum computing, 5G telecommunications, a variety of financial and health technologies, green energy, and additive manufacturing – is therefore crucial. This foreknowledge is already driving international competition in these domains.

The second conclusion, and a very important one from India’s perspective, is that no matter how the global economy unfolds over the next decade, India is likely to remain significantly behind the two major world economies: the United States and China. The chart below shows this plainly. Given reasonable and cautiously optimistic conditions in mind, the best-case scenario would see India emerge as a roughly $7 trillion economy by 2030, by some distance the world’s third largest. But while it would narrow the gap with China, the Indian economy would still remain about one-third the its size. The worse-case scenario from India’s standpoint would be even more daunting. This would see almost a ten-fold differential, and India’s economy still about the same size as Japan or Germany.

Economic growth is important, indeed vital, for the foundations of political power. But over the medium-term future it is no substitute for important strategic decisions that New Delhi takes. In all these diverse scenarios, India has between a 4% and 7% share of the international economy among the G20 by 2030. That margin is important – not least for the welfare of average Indian citizens, and for the overall allocation of national resources. But it does not fundamentally alter the distribution of global power. The choices of how to engage, align, or respond to the other major concentrations of power – the United States, China, Europe, Japan, and Russia – as well as critical regions such as Southeast Asia, Africa, West Asia, and Latin America, will be just as consequential, no matter how fast or slow India grows over the coming ten years.